The traces and remnants of the Cornish clay workings, so graphically evoked by the intensely emotive poetry of Jack Clemo, form the backdrop to the latest 'graphites' of Christopher Cook, which might also be more accurately be described as 'workings', as a whole range of tools and techniques are used to work the surface of these rich and complex images.

Cook's engagement with the distressed landscapes of Cornwall and more recently his residency at the Eden Project has exerted a powerful influence on this work. Those china clay pits - where, in Clemo's words,

Our clay dumps are converging on the land

Each day a few more flowers are killed

A few more mossy hollows filled

With gravel...

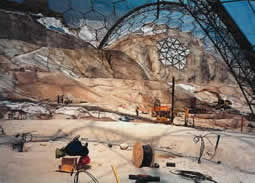

create a scene of desolation, a lunar landscape the colour of bleached bone, where spoil-tip and slurry-pit have ousted nature from the land. Cook's latest series of workings muse upon the return of nature (albeit beneath domed shields of transparent foil) to this stricken place. In Bodelva Pit, nature's sward is being resurrected - the Eden Project's artificial climates now support a variety of plant species (and attendant insects) from around the world.

The graphites are, effectively, a hybrid between painting and drawing - he initially paints the graphite on the support as a liquid, resin-based, pigment, but subsequently 'draws' into and onto it with various implements as it dries, so that, in general, the ground is painted and the figural details drawn. Rather than being built up in layers, as is commonly the case in painting, the images evolve through a reductive process, an elaborate form of sgraffito, so as the graphite is worked, the lighter background shows through. These works also hover between the abstract and the figurative, in an almost Gestalt way, so that what the eye perceives one minute as abstract, may be seen as figurative the next, but then as abstract once again, as we experience a sequence of psycho-perceptual oscillations.

Just as Cook's techniques are reductive, literally reducing the density of the graphite to achieve tonal variations, so his genre as a whole has been reduced, and his earlier, intensely chromatic painting has become wholly monochromatic. There is a certain irony in this transformation, as it happened quite suddenly, following prolonged visits he made to India. We usually associate India with a riotous omnipresence of colour, of course, but while it is chromatically rich and varied, the rhythms and ramifications of most lives are much simpler and more direct, more basic, the rhythms of nature are revered, and the purity of utility prevails. Cook seems to have returned from India questioning the demands of western decadence, determined to simplify his lifestyle, and his decision to paint in monochrome appears to reflect that reductive urge. The quiescence is apparent in the picture plane becoming fluid and dream-like, the surfaces more intimate and seductive.

In his Eden works, Cook has integrated elements from both sides of the Bodelva coin. We see evidence of the now defunct clay-workings, the corrugated flanks of the cone-shaped spoil tips, and the milky lagoon where the slurry lay, but which are now held back and curtailed by the lines of conduits and pipes which mark the advancing works of the Eden Project. Perspective is not only flattened out, but our viewpoint swoops, and veers, the scenes appear caricatured as if at times we are one of those

lazily soaring Indian vultures surveying its domain. Diagrammatic traces of vegetation - the other side of the coin - appear as nature returns, but they are, literally, traceries, like the decorative fronds that formulaically trickle down stereotypical Chinese ink landscapes. The distortion of perspective refrains from betraying whether or not these are creeping, climbing or trailing fronds, as they wriggle and shimmy across the picture-plane.

The dense, lustrous graphite surfaces of Cook's works take on a life of their own, the deliberations of their execution recorded for all to see. While the surfaces are highly worked, the tonal amplitude is narrow, a subtle chiaroscuro of light, mid and dark greys is established, while any sharp contrasts seem to be hard won. In this respect, these drawings take on the demeanour of early photographic prints of Niepce and Daguerre, where a dark veil seems to impose its sombre and shadowy presence. In contrast with the tenuous and tentative realities of those early photographic works, however, Cook's images present the viewer with a textural, decidedly sculptural surface. There is no intention of real depth here though, and they tend towards the mien of the bas-relief, our eyes telling us that their forms are tactile, while logic informs us that they are not.

Cook's approach is, in fact, far removed from that of the plastic sculptor, for here chance is a major-player, these works not only expressions of a process, but also scions of that process. Like process painters, he enjoys a flexibility in the making that allows a mobility of technique to effect a spontaneity and degree of self-generation that invests each image with a clearly unique presence. Sometimes the discoveries that arise out of this process-driven approach drift towards the 'decorative' and at other times towards the 'documentary' and the viewer is made aware of a dynamic interplay between the forms of either persuasion. I don't use the word decorative flippantly here, and certainly not in a pejorative sense, but to describe a lighter, playful mood in these images which injects an element of levity to act as a foil to balance the denser and more descriptive areas, which tend to be more heavily worked, and more physically present. It may seem ironic that Cook uses greys to represent the greening of Bodelva, and what is more, works with a mineral pigment, when it was the voraciousness of the mineral workings that desecrated nature in that place. But this is a sweet irony through which the artist is able to thumb his nose at convention.

More recent paintings have brought a distinctly architectural element into the work. One, derived from an old postcard sent by a friend, depicts the intricately decorated in New York. This painting is virtually photo-real in demeanour, but is curiously off-kilter, leaning to starboard by about ten degrees, vaguely reminiscent of Aleksandr Rodchenko's tilted photographs that elicit a fresh perspective on the world. When I write that it is 'virtually' photo-real, I leave room for the slightly cavalier, loose treatment of certain elements in the scene, where surfaces are hinted at rather than faithfully reproduced, their illusion failing on closer inspection, as with Dennis Creffield's well known series of charcoal drawings of cathedrals, whose indexical faithfulness decreases the closer you get.

The second image refers to a richly ornate in Knokke-le-Zout, Belgium. The chandelier fills the picture plane, with all else, apart from a short section of elaborately moulded ceiling coving, being cropped-out. Mimetically dripping with luxuriant vegetation and other baroque fripperies, this chandelier is finely and exquisitely wrought, in all its intricate detail, simply through Cook's manipulations of tonal variation, making it a masterpiece of execution. Such a rendition of this object imbues it with an alien, brooding presence which seems to give it a purpose other than mere decoration - the uncanny creeps in here, and then completely takes over when you notice that pieces of the chandelier are caught in mid-flight, falling away through the air like crystal rain, associating with the insects that attend the light. This observation - the frozen encounter - also serves to re-inforce the strong parallels between these graphite works and monochrome photography.

Cook is an admirer of the work of the Japanese-American photographer, Hiroshi Sugimoto and there are indeed hints of Sugimoto's aesthetic in these last two pieces, perhaps also in a current work where the familiarity of an Underground escalator is in the process of being transformed through exquisite rendering, imparting a disturbing sense of space which fleetingly invokes the sensation of vertigo. An eccentric image, in which the strange perspectives create an ambiguity to trick our perception, allowing something familiar to take on a new, more unsettling, significance.

It is this dual-identity of Christopher Cook's paintings which gives them their edge - the initial impression of a benign nature, conveyed in low-contrast, is invariably transformed and transmuted upon fuller inspection. There is a saying 'the devil is in the detail', and it seems to be Cook's mandate to create a tension in, or sometimes a leavening of, these images by using the most subtle and diminutive of incongruous or contradictory details. Butterflies are a recurrent motif in the graphites, and in the same way that the flight of a butterfly can trigger a hurricane, the minutest of details here can tip the mood. When looking at his work we should be prepared to expect the unexpected.